I’ve never been one to argue the idea of video games surpassing cinema in many respects. In its short history, the medium has transformed from 8-bit blobs of color backed by MIDI music to glorious high definition masterpieces filled with orchestral scores. Its never been a better time to be a gamer. However, before we celebrate these victories against the naysayers and story-telling pundits like Roger Ebert, we need to realize that there's one overlooked piece of the puzzle that’s missing -- it's something that came to me after re-watching a Coen Brothers classic.

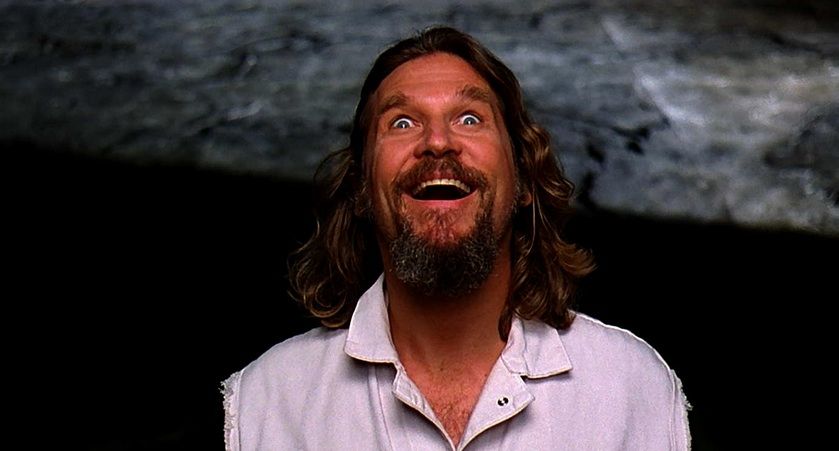

“The dude abides” is just one of many memorable lines scattered throughout 1998's dark noir comedy The Big Lebowski. The film’s main character, “the dude,” played by Jeff Bridges, is, on the surface, the definition of a simple man from a simpler time, but underneath the character adds another layer to the real message being sent across in the film. “The dude” is a representation of something bigger, more profound, and at the same time nothing at all.

It’s something you may not get after your first viewing, but if you're familiar with the Coen Brothers and their body of work, you know that it's there.

After watching a film like The Big Lebowski or even their later works like No Country for Old Men and picking up on all of the little details, you begin to develop your own ideas, meanings, and conclusions. It piques curiosity to the point that -- as a viewer -- you almost have to re-watch it or at the very least dig around to see if others had a similar outcome or connected the same dots as you did. These kinds of interpretations and double meanings are an element from film that has yet to really make the jump to the titles that we enjoy.

Unfortunately for games, the very nature of how they work can act as a hurdle for creators to think outside of the box to deliver these kinds of deeper messages. To get a better idea of what I mean, let's take a quick second to examine gaming for what it is at its most basic level: an enjoyable mechanic, covered in an appealing skin, wrapped in a blanket of story. As players, we’ve been programmed since our very first princess rescue to know that all we have to do is get through it. Analyzation -- for the most part -- is to be checked at the door.

We’re not there to question anything or what a character may or may not represent. We just need to reach the end game, receive some kind of closure (or cliché cliffhanger), and move on to the next one. It seems at this point that even if a game director did take a chance to present something heavy, odds are that it will probably go overlooked, and that’s simply based on how we consume the medium.

The stories in the games we play obviously have the ability to keep their audience engaged through their ups and their downs but rarely -- if ever -- do you find anything deeper than what’s being presented at face value. Cloud Strife from Final Fantasy VII wasn’t a face for modern man in the late 90's. Master Chief’s war against the flood in Halo: Combat Evolved wasn’t a parallel to what was taking place in the Middle East at the time.

There have been a few titles that have managed to pull this off to some extent. Rockstar’s Grand Theft Auto IV is a great example of social and cultural commentary. Unfortunately it seems that most players are too consumed with running amok throughout Liberty City that much of it went unheard or ignored. GTA IV manages to address real issues through its underlying themes of racism, alienation, and the vision of a distorted American dream. It’s delivered in a rather subtle yet clever fashion but it’s most definitely present. For a more obvious example just listen to any of the political talk radio stations found in the game -- some of which are so well written that they could serve as a snapshot of society at the time living in a post 9/11 world.

Rockstar provides us with another example of symbolism in Red Dead Redemption, with their play on the “death of the old west.” The game’s protagonist, John Marston, is on a mission to clear his name and right some wrongs before his troubled past catches up with him. As you make your way through the campaign, you get the sense that both he and his former gang were the last of a dying breed. By the time you watch Marston finally get taken down near the end of the game is when you realize that he is the embodiment of the time period. He is the last of the mohicans (though not a native, the term still works well here), and it’s his demise that would symbolize the death of the old west.

Fans of the Persona series can always turn to the 4th installment to provide this kind of deeper and thought provoking narrative. One of the game's characters, Kanji Tatsumi, struggles with his sexuality and the way that its played out is through battles with alter-ego Shadow Kanji; who terrorizes the character by threatening to "out" him to his friends. Is he or isn't he? That has always been the question, and in the case of Persona 4, American publisher Atlus decided to keep the questions going by stating "We would like everyone to play through the game and come up with their own answers to that question; there is no official answer." Rather than coming out and saying whether or not Kanji was in fact gay, they had their fans make that decision for themselves.

While many games are naturally limited by their mechanics to present hidden messages or opportunities for interpretations, other titles have relied on their endings to help keep things open and up to the player to figure out.

Ninja Theory’s Enslaved: Odyssey to the West was one such game that presented players with an ending that they could kind of see coming a mile away. Yet, when they finally reached the game's finale, they were left even more questions than they began with. The same can be said about JRPG fan favorite, Final Fantasy X. Three years after finding out that Bruce Willis was dead the entire time in M. Night Shyamalan's The Sixth Sense, the developers at Square decided to take FFX a similar route as gamers were left bamboozled after finding out their beloved Titus would share a similar fate. While it still isn’t sure whether he was dead, dreaming, or even existed, the games memorable ending (and the clip that followed) allowed for plenty of room of interpretation.

A more recent and rather tumultuous example of this kind of ending can be found in 2012’s Mass Effect 3. While I’m going to completely avoid the fallout that would follow the game’s release, it’s clear that the original intention, as stated by the game’s director, Casey Hudson, was to deliver “a story that people can talk about after the fact.” Without going too much into it, I think we can all agree that the studio hit its mark. It should be noted that, while it seemed as though the entire internet was busy readying the pitchforks and torches, there were many players who chose to accept the ending for what it was and with that decided to make their own interpretations and build on the fiction themselves with some good old imagination. Who would have thought, right?

Say what you will about these kinds of endings, but if you look at the titles that incorporate them you’ll see one thing in common: these games -- more often than not -- are among the most memorable. This open style or “gainax ending” (as TVTropes refers to them) may leave a bit to be desired by some fans, but, at the same time, it allows players to create their own closure for whatever journey they’ve just completed.

While I wish the same can be said about the stories in the games we play, unfortunately for now at least, those searching for more thought provoking elements and double meanings (outside of a game’s ending) must still rely on cinema to replicate the effect on a consistent basis. Is it bad that, for the most part, games are presented with a “what you see is what you get” style of delivery? Not necessarily, but when you consider all of the advancements in video game storytelling, it’s almost a shame that we don’t see these kinds of chances being taken by those that we place on a plateau of digital creativity.

As a culture we may not be ready for so much substance. After all, we’re knee deep into a console generation that relishes in rehashes and sequels, and as consumers who should expect something more, we eat it up anyway. Perhaps there are developers out there that want to take these kinds of creative chances. However, just like “the dude” in the Coen Brothers film, for these developers, it’s much easier to just be, and go with the flow -- not over think things too much. You can’t be mad at “the dude” because, at the end of the day, it’s what the masses want. It’s what’s expected. We're the reason why “the dude abides.”