The Playstation 2 wasn't a platform renowned for its western-style RPGs. You were short on options if you were the kind of adventurer seeking dwarves and elves and half-elves traversing deep dungeons by torchlight before emerging with their loot to trade in the city, where you'd go on to get served ale and quests by a busty bar lady in a fuggy tavern called The Regal Horseshoe, The Prancing Pixie, or The Spread-Eagled Goblin... or something.

And while I've talked pretty recently about a rare find of a western RPG that came out on PS2, there was also an unexpected RPG heavy hitter that came to Sony's console a little later. In 2001, Baldur's Gate: Dark Alliance arrived on PS2, containing all the tropes outlined in that first paragraph - busty bar lady and all.

Dark Alliance went along with the prevalent stereotype at the time that console gamers had the attention span of Slaughterfish (which is marginally longer than that of a goldfish, I've been told) and wouldn't be able to handle a complex RPG in the vein of the first two Baldur's Gate games. It was a Diablo-style ARPG, with a focus on hacking, slashing, masses of loot, and a heavily streamlined levelling and progression system.

The thinking, according to Interplay Senior Producer Eric DeMilt, was simple. He told me in an interview last year, "My feeling was, 'hey, here's our biggest IP and we don't have a console offering for it. Here's a team with really great tech that's really into this space. Why don't we talk to them about doing a PS2 and Xbox version?"

It was actually a pretty great game for the time, built by a 13-person team in a mere six months on a powerful in-house engine made at Snowblind Studios called the Snowblind Engine. It had incredible water deformation, silky-smooth frame rates, and plenty of lovely little touches like individually rendered coins dropped by enemies, which meant that the amount you picked up in a pile reflected the number you received in your inventory.

Baldur's Gate: Dark Alliance 2

The combat felt great too, with satisfying squelchiness as battle axes cleaved rats and goblins in two, fire spells caused enemies to go up in convincing blazes, and spell effects glimmered . The shoehorning of a jump button and various platforming elements is, in hindsight, kind of quaint, showing the game to very much be a product of a time when such things were deemed important boxes to tick in consoles games. It's as if the business-minded box tickers, thinking 'Console gamers are simple people. They don't know what an RPG is, but they do like platforming stuff like Crash Bandicoot or Mario, so let's have some of that.'

Dark Alliance sold over a million copies across the PS2, Xbox, and GameCube, which was enough to warrant a sequel. In fact, at this time publisher Interplay was getting into serious financial difficulty. The publisher sold off Baldur's Gate developer BioWare, and had to cancel new PC entries in the Baldur's Gate and Fallout series. Console games seemed to be a comparatively quick and easy way to make money, and so Interplay began looking at a sequel to Dark Alliance.

The problem is that Dark Alliance developer Snowblind was only contracted for the first Dark Alliance, and following the game's release the talented studio was quickly snapped up by Sony Online Entertainment to make Champions of Norrath - an action-RPG spinoff from the popular MMO EverQuest. This left Interplay to use one of its legendary internal studios, Black Isle Studios, to make Dark Alliance 2.

This created a fascinating split, where two games with a similar style were being built on the same bespoke engine at the same time by two different teams. Baldur's Gate: Dark Alliance 2 and Champions of Norrath came out within a month of each other at the start of 2004, forking off from the compelling ARPG formula started by Dark Alliance in 2001.

The games could've been total overhaul mods of one another, with the same combat system, engine, art style, even UI fonts. But they did have some key differences. Dark Alliance 2 (whose unexpected PC port I reviewed recently) introduced a far more diverse and compelling roster than its predecessor, complete with individual character quests, dialogue, and so on. Being a Black Isle game, it also introduced some nods to its PC lineage, with things like an overworld map you could travel across and some interesting crossovers with Baldur's Gate lore (though being a smelly little console game, it was never deemed fit for Forgotten Realms canon).

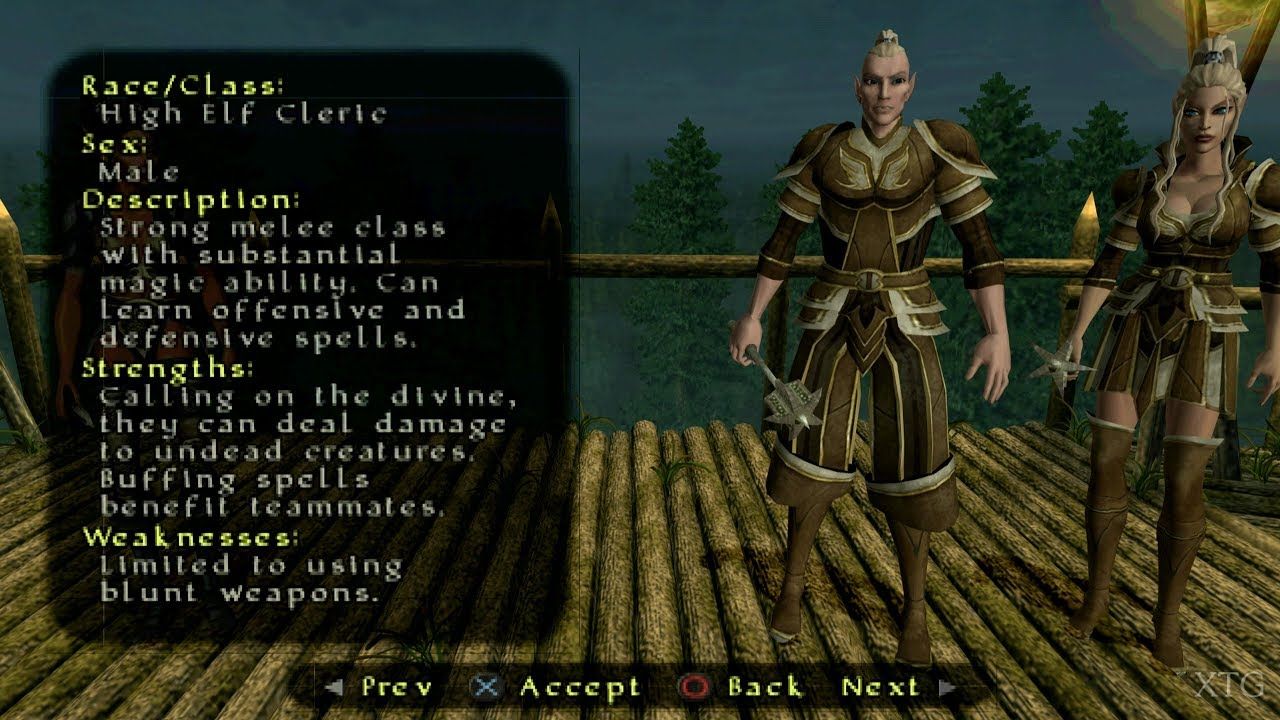

Champions of Norrath, meanwhile, was a beast both similar and altogether different. Instead of giving you preset characters with their own stories, it let you create your own character from several templates based on Everquest races and classes. So you could be a Dark Elf Shadow Knight, for example, a Barbarian Fighter, or an Erudite Wizard, picking their sex, as well as different hair styles, faces and tattoos. It was customisation at the expense of characterisation, and whether it was better or not didn't matter so much as the fact that it felt so parallel to Dark Alliance 2.

In some ways, Snowblind's greater experience with their own engine was telling in Champions of Norrath (and its 2005 sequel, Champions: Return to Arms). The game bumped the co-op up to four players (and utilised the PS2's burgeoning online play feature), and the EverQuest environments were a little more flashy. The treetop towns, rolling desert dunes and even tropical climes of Norrath felt more vivid and varied than the more classical fantasy setting of Dark Alliance 2.

Some of the voice talent from the original Dark Alliance, such as Cam Clarke and Tony Jay, went over to Norrath as well, though Dark Alliance 2 voice talent like Alan Shearman, Alan Oppenheimer (aka Skeletor from He-Man) was nothing to be sniffed at either. Black Isle's RPG chops were also reflected in Dark Alliance 2's slightly deeper levelling and skill system.

The 4-player online and local co-op in Champions of Norrath was pretty much unparalleled at the time

Whichever of the two games you preferred (why not both?), their coexistence was bizarre, like the convergence of two separate timelines - one in which Snowblind kept its engine, the other in which Interplay kept the rights to it. And if you ask Snowblind, then these two games shouldn't have both existed. When Snowblind got wind in 2003 that Interplay was continuing to use the Snowblind Engine to make its own games, it launched a legal dispute, claiming that Interplay should've obtained consent to use the engine. The dispute ended in 2005 with something of a pyrrhic victory for Snowblind. It was agreed under the terms of the agreement that Interplay could continue working with already-made games in the Snowblind engine, but wouldn't be able to use it for future games.

This exacerbated Interplay's financial woes, and meant that they had to cancel development of Baldur's Gate: Dark Alliance 3, as well as Fallout: Brotherhood of Steel 2, the sequel to another similarly styled hack-and-slasher set in the Fallout universe (which, it has to be said, was far inferior to Baldur's Gate or Champions). The Snowblind Engine's shelf life didn't last much beyond 2005 anyway, with the last game made using it being Justice League Heroes, released by Snowblind Studios in 2006.

We don't know whether Interplay genuinely believed it 'part-owned' the Snowblind Engine, or if in their financial turmoil they were just trying to see how many games they could release on it before they got caught. Given the recent re-releases of Baldur's Gate: Dark Alliance 1 and 2 on modern consoles and PC (at a whopping $40/£30, no less), it looks like Interplay got quite a lot of mileage out of the Snowblind Engine. You have to wonder of Daybreak Game Company, the current holders of the EverQuest IP, are looking over at these games and weighing up a similar return for the Champions of Norrath games, which would let today's gamers experience this interesting RPG rivalry from the PS2 era.