One of the most important shooters of all time, BioShock, has turned 15. Playing it today, it doesn't feel like a 15-year-old game, and I realise that's in large part because so few games have attempted to really follow in its footsteps. It's a predecessor to certain genres that would come later - like the 'walking sim' - and it was the first blockbuster game that showed the medium to be capable of seriously exploring some high-minded ideas, but that mix of emergent gameplay, eccentricity, and worldbuilding where you piece together the story of a fallen city through desecrated rooms, meticulously positioned corpses, and brilliantly delivered audio diaries hasn't quite been repeated.

It didn't come as much of a surprise that when I reached out to BioShock creator Ken Levine, he was unaware that the game was coming up to its 15th anniversary (much though I like the idea of Levine, every five years since 21 August 2007, pouring himself a glass of bourbon in a grandiose Deco bar and raising a glass to a portrait of Andrew Ryan - Rapture's founder.)

When I ask Levine the simple opener of whether it feels to him like BioShock came out all of 15 years ago, he gives a diplomatic 'yes and no' answer, adding that in terms of the industry itself, BioShock feels relatively young. "It was a much bigger delta, I think, between System Shock 2 [1999] and BioShock than it was between then and now because at some point the switch flipped from games being a real niche," he tells me. "Games were the kind of thing that only really weird nerds like me would play when I was a kid, and by the time BioShock came out it had already achieved a cultural presence that it didn't have in 1999."

Coming out in the wake of games like Half-Life 2, Halo, and several Call of Duty games, 2007 was the heyday of the realistic (or at least semi-realistic) shooter. Irrational and Levine even contributed to this phenomenon with the excellent tactical shooter SWAT 4. But with BioShock's heavy focus on story and atmosphere rather than realistic combat and linear progression, it didn't really fit the conventions of the time.

Yes, it was a first-person shooter, but really that was just a marketable framework for something far more ambitious. Clearly, Levine had learned from the poor sales of the more RPG-leaning System Shock 2. "We thought System Shock 2 might have bounced off people because they just couldn't get their heads around it," he says. "And so we tried to find some way to communicate BioShock in ways that people understand. First-person shooters were just a shorthand, and back then first-person experiences were first-person shooters, so we thought 'OK. How can we expand that vocabulary to do a little more?'"

I was going to mention the rise of 'walking sim' games to Levine, but he beats me to it when he points out that since BioShock games like Gone Home have redefined what can be done in the first-person framework. Gone Home, along with others like Dear Esther, Edith Finch, and SOMA, seem relevant because they're so heavily informed by BioShock's means of storytelling - that atmospheric mix of exploring non-essential corners of the game world, snooping through drawers, listening to soundbites, and the occasional elegantly crafted scripted sequence (all while not breaking from the first-person view, of course). Gone Home, in fact, was made by former Bioshock developer Steve Gaynor, who went so far as to tell IGN that both games are set in the same universe.

Clearly, BioShock was a big influence on this genre that emerged some years later, but for a big-budget first-person game to not have combat aplenty in 2007 would've been unthinkable. Had the industry been as welcoming to non-combat first-person experiences as it is today, would BioShock have gone for less of a shooter focus, or even ended up a non-combat game? "Steve [Gaynor] took his love for BioShock and answered the question ‘do you need the combat’ with a 'No’, and I think he was very successful," says Levine. "I'm a bit more old-school. I like gameplay, as a developer I like game systems a lot. If I didn't have the resources and I really had to make those choices, I might make one of those games - I like them - but for me personally I think I would miss the game systems."

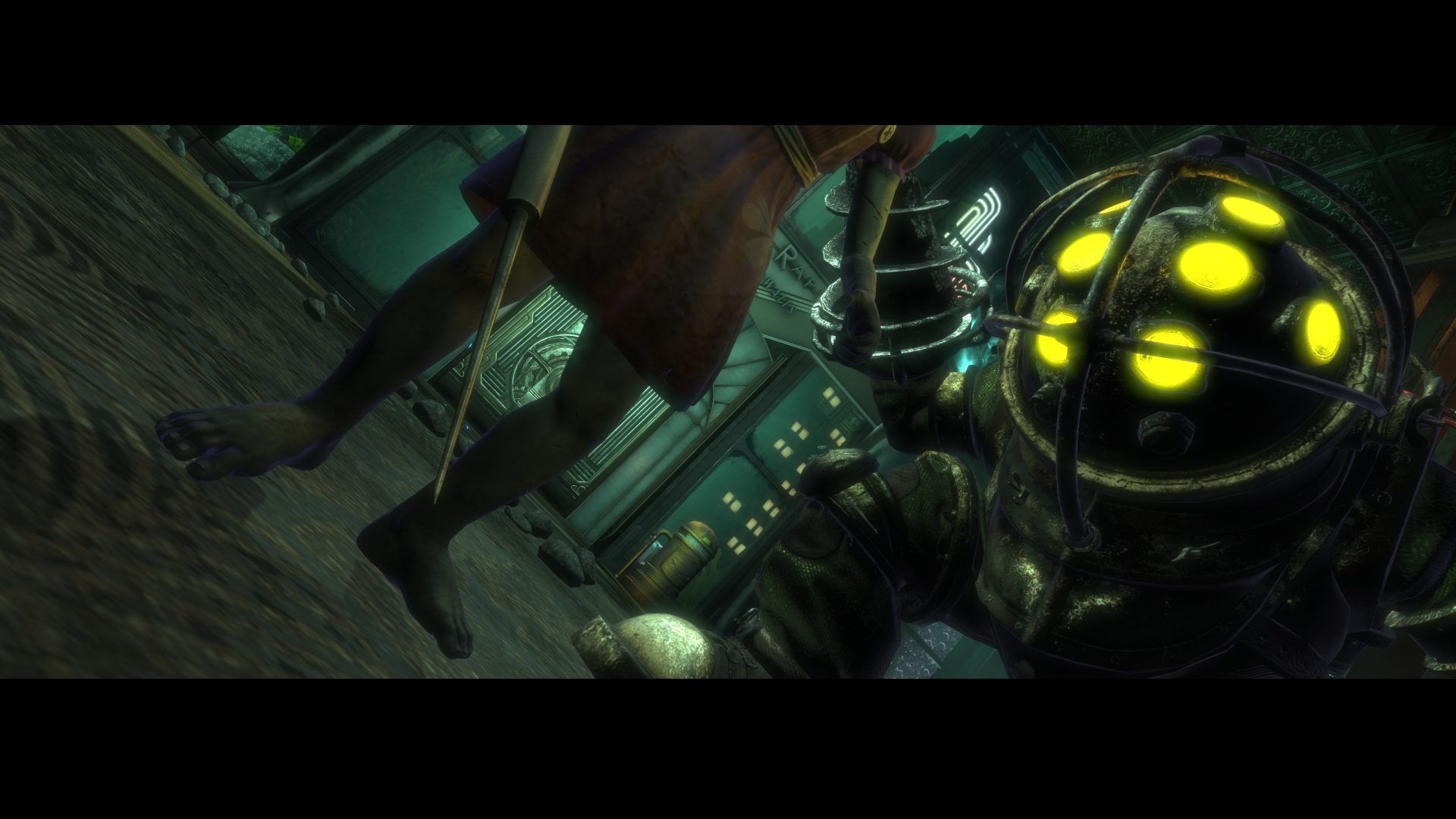

BioShock wouldn't be the same game without its core system, which is based around a trinity of Aggressors (Splicers), Guardians (Big Daddies), and Gatherers (Little Sisters) wandering the damp, decrepit halls of Rapture. It's a system that gives the game endless macabre allure, as watching these three forces collide - or more specifically Big Daddies colliding with Splicers that dare to approach the Little Sisters - remains an incredible spectacle of emergent madness. Throw Rapture's security systems into the mix too, which you can turn to your side to take on both Splicers and Big Daddies, and you can simply sit back and watch the carnage unfold (though the lack of stealth mechanics meant that you often got spotted and pulled into it yourself).

BioShock is a game that could engage you with multiple stories at once. You could be listening to an audio diary about a cold-hearted scientist, Dr. Suchong, and his desire to genetically engineer children to 'skip' childhood (before he meets his deserved demise at the hands of his own project). At the same time, you could behold the oddly poignant and primal spectacle of Big Daddies wandering around with Little Sisters, who seem every bit the innocent little girls despite their tendencies to suck ADAM out of corpses using giant syringes. Then of course you have Atlas and Ryan talking in your ear, driving the main narrative alongside a few select characters you meet, usually behind impenetrable glass screens, until those bloody face-to-face finales.

The game is finely balanced between emergent play, non-linear storytelling, and well-choreographed scripted events, such as a Splicer with a pram that you first see via an ominous shadow on the wall, or a Houdini Splicer who lures you into a fecund maze in the Arcadia garden district to the tune of escalating organ music. Keeping all these elements in harmony, according to Levine, comes down to pacing.

"There are many skills I don't have as a developer, but one I do have is the ability to keep things separate, to always play the game as a gamer, so it's really about pacing," he tells me. "I use my instincts as a player of what I would find interesting, and then we move shit around all the time, because sometimes we're like 'this is way too heavy on this or we're way too heavy on that,' and you know that because you get bored or you get overwhelmed."

A big part of keeping every encounter engaging is character - whether it's listening to an audio diary next to a dead body and a spilled glass of whisky, or bracing yourself for battle against a gang of roaming Splicers while ghostly jazz music crackles over the Rapture megaphones. "Deep down, what are the Splicers? They're an AI that shoots at you and does a bunch of semi-interesting things," Levine says matter-of-factly. "But what I thought was going to make the Splicers poignant was their lost humanity." We talk a bit about the mutants in System Shock 2, which implore you to "RUN" as they charge you with a crowbar, then move onto a scene from Saving Private Ryan that has always affected and inspired Levine.

"There's a scene where the Jewish soldier gets into hand-to-hand combat with a German soldier and the German soldier ends up knifing him to death," he recalls. "It's the hardest thing to watch because he's telling him ‘Shh, it's OK’ like he's trying to make it easier on him. I get kind of emotional just thinking about it. It adds a weird humanity. It's freighted with so much stuff."

While the Splicers don't afford you quite the same cold comforts as they attack you, there is still a humanity there. Out of combat, you'll hear them sobbing about their loneliness or reminiscing about past loves, before they burst out in apoplectic rages over the injustice of romantic rejection or the current sorry state they're in. The Splicers are pretty abhorrent and give the impression of mostly having been not-so-great people, but each of them is a strong character with a relatable inkling of humanity.

I use my instincts as a player of what I would find interesting, and then we move shit around all the time.

Levine reveals that there is no group-based AI to the Splicers. When I point out that this conveniently overlaps with Rapture's principles, and ask whether perhaps their individualistic AI was intentional, Levine chuckles. "I think it was intentional since it would have been a lot more work and money to include it!"

On the subject of Rapture's ideology, I suggest that BioShock was the first major 'political' game, in the sense that the entire narrative - and many of the mechanics - are built around a critique of Ayn Rand's Objectivist ideology, which posits a society completely unregulated by government or state and instead dictated by absolute free-market capitalism. This would ostensibly facilitate society's greatest and most entrepreneurial individuals to innovate in key fields like business, science, industry, and technology without the barriers of oppressive regulation. Interestingly, even though Rapture is closely analogous to the Galt's Gulch community from Rand's book Atlas Shrugged, Levine admits he's never read the whole thing, and much prefers the narrative flair of another of her works, The Fountainhead.

"Atlas Shrugged is much less of a great story. At one point, it has this like 40-page speech in it," Levine says. "But The Fountainhead was more of a potboiler than a political book. It's the story of this guy and you have this 'big enemy', this critic, all these conflicts, there's this sexy romance story. It's kind of silly in a lot of ways, but I think the reason it's so popular is that, like BioShock, it works in this purely potboiler way."

Levine steers clear of a definitive judgement of Objectivism, though he says that over the years objectivists have said he's shown a good understanding of the principles, even though Rapture is a demonstration of that ideology going to hell when applied to actual people. This leads us to what could be a big part of BioShock's enduring conceptual appeal. Its exploration of Objectivism through the grandiose Deco setting of Rapture and its people doesn't so much criticise the ideas as much as it criticises the inevitably flawed human implementation of those ideas.

Having discovered Rand's works mid-development, Levine has no great attachment towards or against Rand's controversial writings, though it's interesting to see how certain elements that appeal to him chime with the kind of mentality that helped him conceive BioShock - and Ryan conceive Rapture - in the first place. "I think there's a lot of interesting stuff in terms of individualism," Levine muses. "I liked the idea of the artist, the uncompromising artist who didn't have the critic in mind when they made the thing, and they weren't trying to make the thing for the critic. You have to make the thing for yourself."

While it's tempting to hold BioShock as an illustration that Objectivism is the road to hell, its ideas can be applied far more broadly. Levine says that he's "suspicious" about ideology, and that for him the binary 'with us or against us' narrative surrounding the Iraq War in 2003 played a big part in his growing cynicism towards it.

"My games are interested in that intersection of ideology on the page and people in reality, and what happens when these high-minded principles meet reality," says Levine. "I think ideologues tend to forget how messy things are. Rapture was an example of that - you have this ideological schism and quite often the ideology is a map for blind ambitions." In BioShock's case, it ends up not being the true ideologue, Andrew Ryan, who is all-powerful, but Fontaine - the man capable of using an ideology, a movement (in this case a sort of socialist revolutionary fervour) for his own gain.

I liked the idea of the artist, the uncompromising artist who didn't have the critic in mind when they made the thing.

BioShock may have pioneered the exploration of politics in gaming, but it continues to be one of the most level-headed and successful examples of it. It's a game that's a game first, and an excellent one at that; its core design came first, and the ideological critique came later in development incidentally and organically - happened upon by someone who was simply curious to explore these ideas through a medium that, until that point, wasn't really associated with such ambitious pursuits.

Levine suggests that the reason BioShock did this so well is that he had no bone to pick with Rand's ideas going into the game, and that he's far more interested in raising questions than pushing players towards certain opinions. Ever avoidant of applying labels to BioShock, he concludes: "My games are political, I guess, but they're not there to provide the answers to anybody."