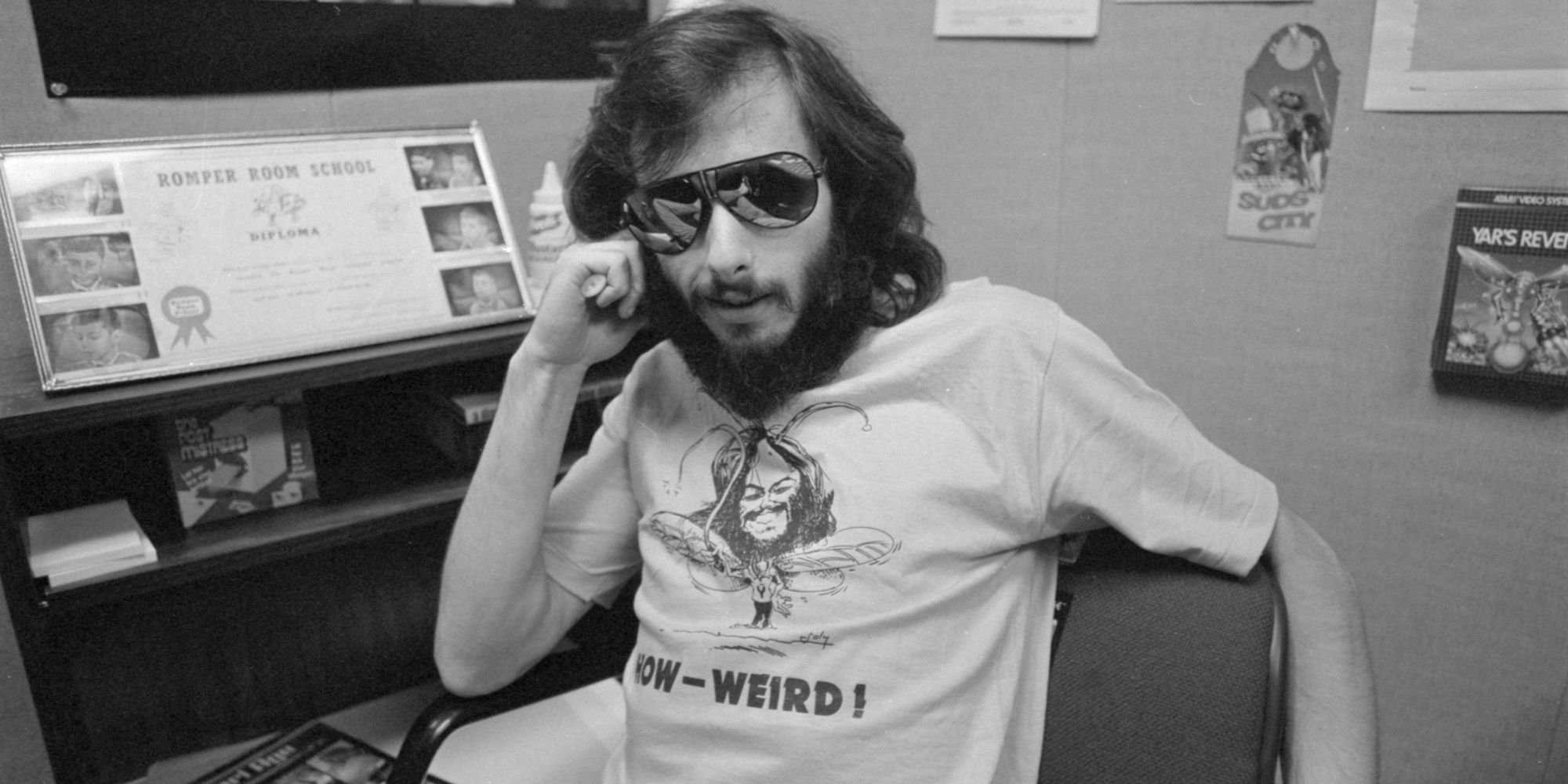

In time for the 50th anniversary since Atari was founded, one of its key developers Howard Scott Warshaw recently published a book, Once Upon Atari: How I made history by killing an industry, charting those final tumultuous years at Atari before the video game crash of 1983. This interview with DualShockers touches on some of Warshaw’s achievements and stories from that time, but for the full story you can buy the book on Amazon.

“We called it the ‘Sprinkler Lobotomy,’” recounts Howard Scott Warshaw when I ask him about the kinds of shenanigans in-house developers got up to at the height of Atari’s powers in the early 80s. Tod Frye, developer of the infamous Atari 2600 version of Pac-Man, learned to suspend himself between two walls in a narrow corridor, and shimmy himself along it around six feet in the air. When he wasn’t running down the corridor banging on walls or making games, he was practicing this move, until one time it went terribly wrong. “He couldn’t keep going if someone opened a door, so one time when that happened his head happened to be near one of those round water sprinklers with the sharp edges. He jumped up a little to release himself, gashed his head on the sprinkler, and fell to the ground covered in blood, before being rushed off to hospital.”

Frye recovered from his bizarre injury, but in some ways it was indicative of those heady final years at Atari before the video game crash of 1983. The years leading up to that were dizzyingly successful, fuelled by the talents and eccentricities of its developers before everything came crashing down, like Frye, with unimaginable speed and brutal suddenness.

Warshaw arrived at Atari in 1981, leaving behind a comfortable but uninspiring job at Hewlett-Packard. Atari had recently been purchased by Warner, but still had its creative vigor, and hadn’t yet moved over to a more marketing-and profit-driven schedule that would ultimately contribute to its downfall. “When I started, all that counted was that you created something that people enjoyed,” Warshaw tells me. “It didn't matter how you did it, it didn't matter if it was structured well, it didn't matter if other people approved of how you approach it; it only mattered that you created something interesting, engaging and fun on the screen, and that's what I was all about.”

Where game development teams consisted of maybe five to a couple of dozen people in the 90s, with that increasing to the hundreds and even creeping over 1000 today, back then at Atari it was one person to a game. The office was shaped like a quadrant, on the interior of which was a mass of development stations that developers walked up to, inserted their floppy disks containing their games, and set to work.

“One person, one game, that was it,” recalls Warshaw. “There was a beauty to that, and also a sense of responsibility that could be crushing at times, because if the game worked, it was all yours and it was brilliant and it was exciting. And if the game wasn't working then, well, it was still all yours.”

These being the nascent years of the games industry, many of the developers at Atari had other jobs. There were painters, musicians, engineers (Sprinkler Lobotomy patient Tod Frye worked in construction). Everyone there was a hybrid of some sort, bringing their own eccentricities and creativities to the workplace. There was plenty of creative osmosis in this environment, with developers sharing ideas on new effects, new bits of code, and ways to maximise the puny 4000 byte (4KB) memory limit on each game.

Warshaw himself got off to a flying start at Atari, making Yars’ Revenge, which would go on to become one of the best-selling games for the Atari 2600. It was originally going to be a port of the coin-op game Star Castle, but Warshaw dug his heels in and insisted this wasn’t going to work, because the console’s hardware was far weaker than arcade cabinets at the time (this discrepancy was evident in the critically panned Atari 2600 version of Pac-Man released in 1982).

So Warshaw got to create his own game–a relatively complex one that cast you as an insect (the titular Yar) trying to break through a barrier to destroy a cannon/’Swirl.’ When you destroyed the cannon, a spectacular explosion would fill the screen This was supposedly the first on-screen explosion depicted in a game–a shimmering rainbow of colours that covered the whole screen before slowly subsiding. For the time, it was an incredible visual effect.

“What’s cool there is that I figured out a way of using the code as graphics,” Warshaw tells me. “So instead of making separate graphics data and taking up extra space, I just took the actual procedural code and threw it in the colour and graphics registers, which effectively randomised both the visual and the colour. I then streamed that up and down the strip of the screen and that made this glittering strip in the centre of the screen.”

Warshaw also claims, with some pride, that Yars’ Revenge was the first game with an actual backstory, involving houseflies that snuck onto an interstellar spaceship, mutated due to years and years of radiation, then took over the ship and colonised their own solar system. These Yars, as they became known, then turn vengeful when a cosmic monster known as a Qotile comes along and destroys one of their planets. So the game charts the Yars’ vengeful mission to destroy the Qotile monsters. Even that radiant explosion has an explanation: “It’s actually the ionic remnants of the destroyed planet,” Warshaw points out.

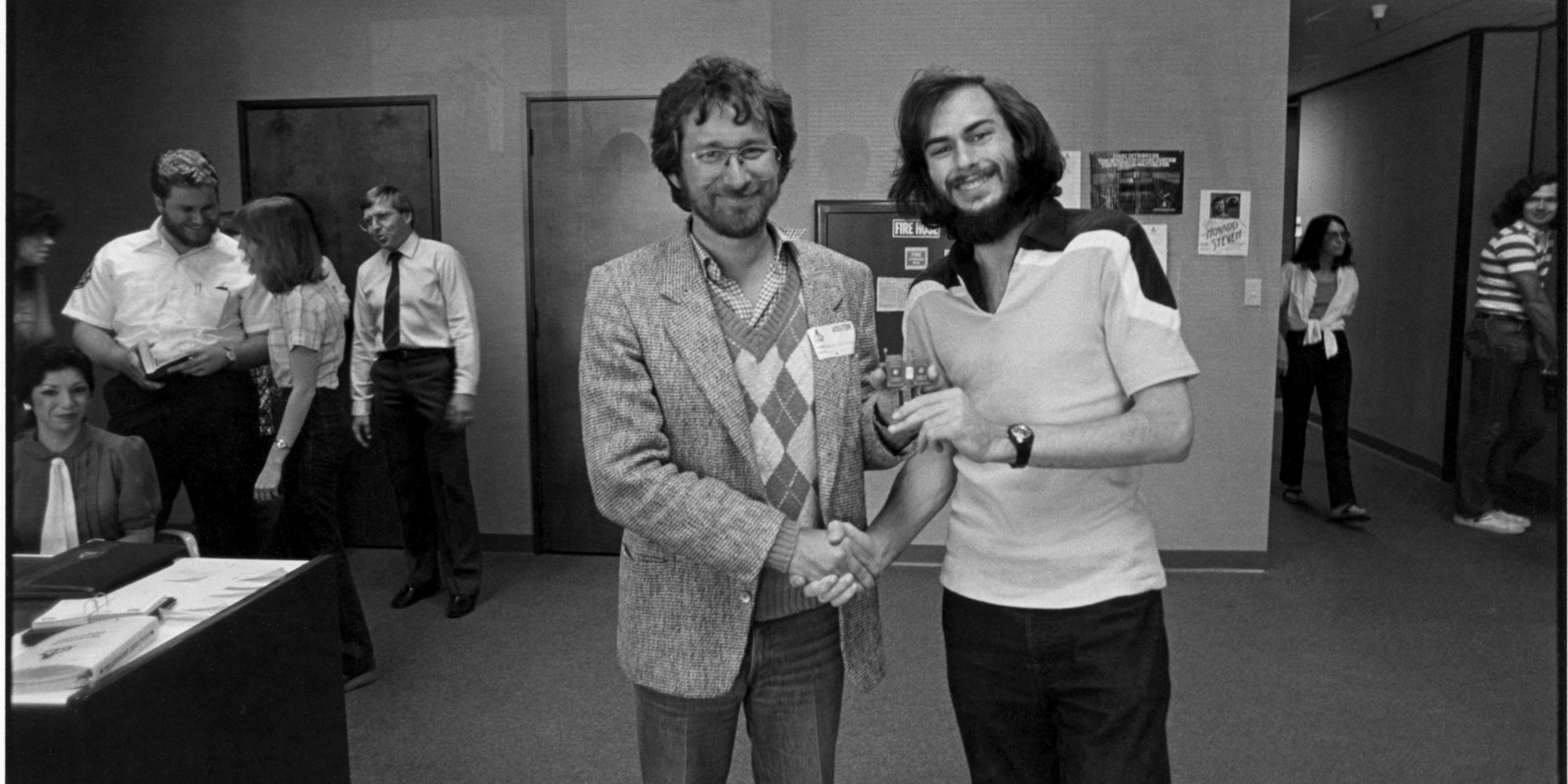

As Warner pushed for Atari to make more licensed games, Warshaw got the opportunity to make a tie-in game to Indiana Jones: Raiders of the Lost Ark, which involved him meeting Steven Spielberg in person to pitch the game. “I showed him Yars’ Revenge, and he liked that, then we talked some, but what I think really clinched it was when I explained to him my theory that he himself is actually an alien,” Warshaw chuckles, while holding back on the exact details of this ‘Spielberg as Alien’ theory for his book.

The Raiders game was released in 1982, and was another success story for Warshaw, but the squeeze to churn out games faster and faster came to a head soon after its release. Straight after Raiders, Warshaw was approached to make an Atari 2600 video game tie-in for E.T., with the stipulation that it had to be released in time for Christmas 1982, giving him just five weeks to make the game.

Despite the relative simplicity of Atari 2600 games to our modern eyes, a typical game for the console would still take 7-10 months to make, so to have just five weeks was both unprecedented and absurd. Warshaw was aware of these conditions before jumping into the project, and was even advised against it by some of his superiors.

So what compelled him to do it?

“I could not resist a challenge,” he says. “I made some special negotiations with them because I knew to attempt something like this was crazy to begin with so I wanted to make sure I was covered for it. I just needed to do it though, needed that challenge. Yeah, and the rest is ignominy.”

It’s well documented that E.T. was an industry-scale disaster. Sales fell far short of shifting the four million produced copies of the game, countless copies were returned, and Atari not only failed to recoup costs for production and licensing, but was left staring into a financial abyss (which, in fairness, was only partly down to E.T.’s failure).

Warshaw, however, has no regrets, and maintains that for the time he had to make the game it wasn’t all that bad. “Doing a game this quickly is not about programming faster or better than anybody ever programmed before. It's about designing something to be done in that time frame, and fortunately I knew enough about the system to know what kind of things I could get done quickly,” he says. “I committed to five weeks and I did it. It's not the greatest game in the world, that's for sure, but many people have assured me it's not the worst by any means either. What’s definite is that it's the fastest game developed for the 2600.”

E.T. was by no means the sole cause of the video game crash of 1983, but it became its symbol. Recording a $536 million loss by the end of 1983, Warner sold Atari to Commodore’s Tramiel brothers in 1984, who shifted Atari’s focus away from home consoles towards personal computers.

Warshaw was at Atari during its crash, witnessing the company shrink from 12,000 to just 200 employees. Seeing the writing on the wall, he decided to walk away from the company. “They wanted to make a home computer to compete with Commodore and that wasn't really what I wanted to do,” remembers Warshaw. “At that point I realised my gravy train had dried up, so I walked off into the sunset. It was a sad day when I left, incredibly sad, because those were some of the greatest years of my life.”

With not much left of the US-based video games industry in 1983, Warshaw left games development to pursue other interests–photography, documentary filmmaking, and psychotherapy among them. While he’s happy with how his life unfolded post-Atari, he admits that if the industry hadn’t effectively ceased to exist at that point, then he “certainly would have been motivated to” keep working in it.

But 40 years on, in a quintessential example of ‘Never say never,’ Warshaw is making an unexpected return to video games, and the game that instantly cemented his status as an Atari legend. “I’m working with Atari on a sequel to Yars’ Revenge. It’s going to be for broader distribution, will be much more balanced, and elaborate on the story.” With records like ‘first video game explosion’ and ‘first video game backstory’ already under his belt, it looks like ‘Longest span of time between an original game and a sequel’ could be the next record for Warshaw to break.

If you want to dive deeper into the video game crash of 1983 from the perspective of Howard Scott Warshaw, head over to the site for his book Once Upon Atari.