Listening to Tim Cain and Leonard Boyarsky talk about their experiences making Fallout, it's hard not to get intoxicated by their enthusiasm, which endures even 25 years on from when the game was made. As one of them begins outlining a particular story from the game's development, even before any of the details have been made explicit, the other one is already chuckling to themselves in anticipation of what's about to be said next.

Having worked together on Fallout at Interplay, on Arcanum and Vampire: The Masquerade - Bloodlines at Troika Games, and now on various projects at Obsidian, there are few developers as synergised as these two. That unbreakable bond, however, was first established way back in 1995, when Tim Cain was given the green light at Interplay to make an RPG for the PC that used the GURPS tabletop game license.

The story of Cain doing a call-out to see who at Interplay was interested in getting involved in this project; with the promise of pizza and the opportunity to work on something from the ground up, Cain expected plenty of people to show up, but only five or six did.

What's less known is that these early meetings for what would eventually become Fallout had to take place on the developers' own time. Interplay didn't mandate devs to work on this game, it allowed it, so long as it didn't interfere with their other work. Interplay was pursuing a D&D license at this time and had multiple projects on the go, so this GURPS-based RPG simply wasn't a priority. "I think the Fallout team self-selected, in a way," says Cain. "It was the people who were super-passionate about making a game. People who didn't feel that way were like 'I'm not going to stay late to do this.'"

"We had an opportunity and we were willing to spend extra time doing it," adds Boyarsky. "Interplay wasn't saying we have to work late, but more like if we wanted this to happen, here's what we had to do."

One of the common misconceptions about Fallout is that it was designed as a spiritual successor to Wasteland, the seminal post-apocalyptic RPG made by Interplay founder Brian Fargo in 1988, but Cain and Boyarsky insist that it in fact had almost nothing to do with it. "The natural connection that people make is that it all grew out of Fargo's Wasteland and when he heard we were going post-apocalyptic, he was really into us making it Wasteland 2," says Cain. "He couldn't get the rights to it in the end, and we said it sounded like a great idea, but it didn't direct our trajectory at all. We didn't make any changes like 'Oh, this is going to be more what Wasteland was.' We were still making our game."

Boyarsky even confesses he never played Wasteland, even though copies of it were handed around the office. "I had a peak Pentium 486, and the game was unplayably fast due to the unbridled processing power of my machine."

In fact, Fallout (well before it was called that) went through several permutations before settling on the post-apocalyptic theme; it started off briefly as a fantasy RPG, before moving onto a time travel adventure, and eventually a sci-fi alien invasion setting, which is where the Vault idea originated. "We had this alien invasion, the world had been destroyed, and survivors are hiding in underground bunkers," says Cain. "That's when we went post-apocalypse, and we kept the vault idea. I remember that being a big stepping stone."

The feel of their post-apocalyptic RPG was starting to come together, though it wasn't on anyone's minds to do something the world hadn't seen before. Boyarsky openly describes the early going as "some sort of Mad Max ripoff," and the reason it evolved beyond that was due to the team's own personalities "taking over in a weird way." Those Mad Max influences are still there - the grimy dieselpunk aesthetic, the jagged leather armour, the arid, sandy state of the game's wasteland - but of course the game went far beyond that.

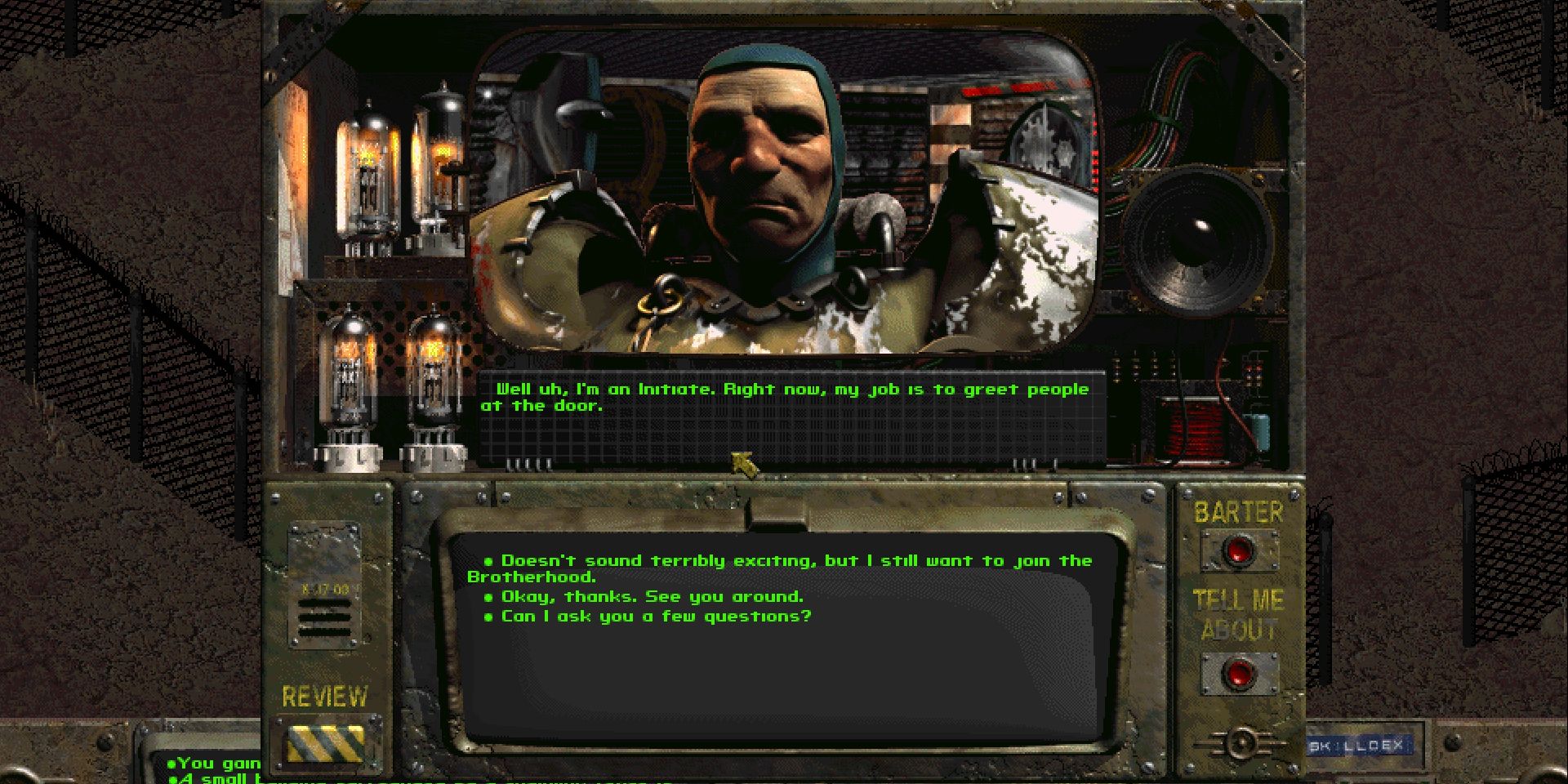

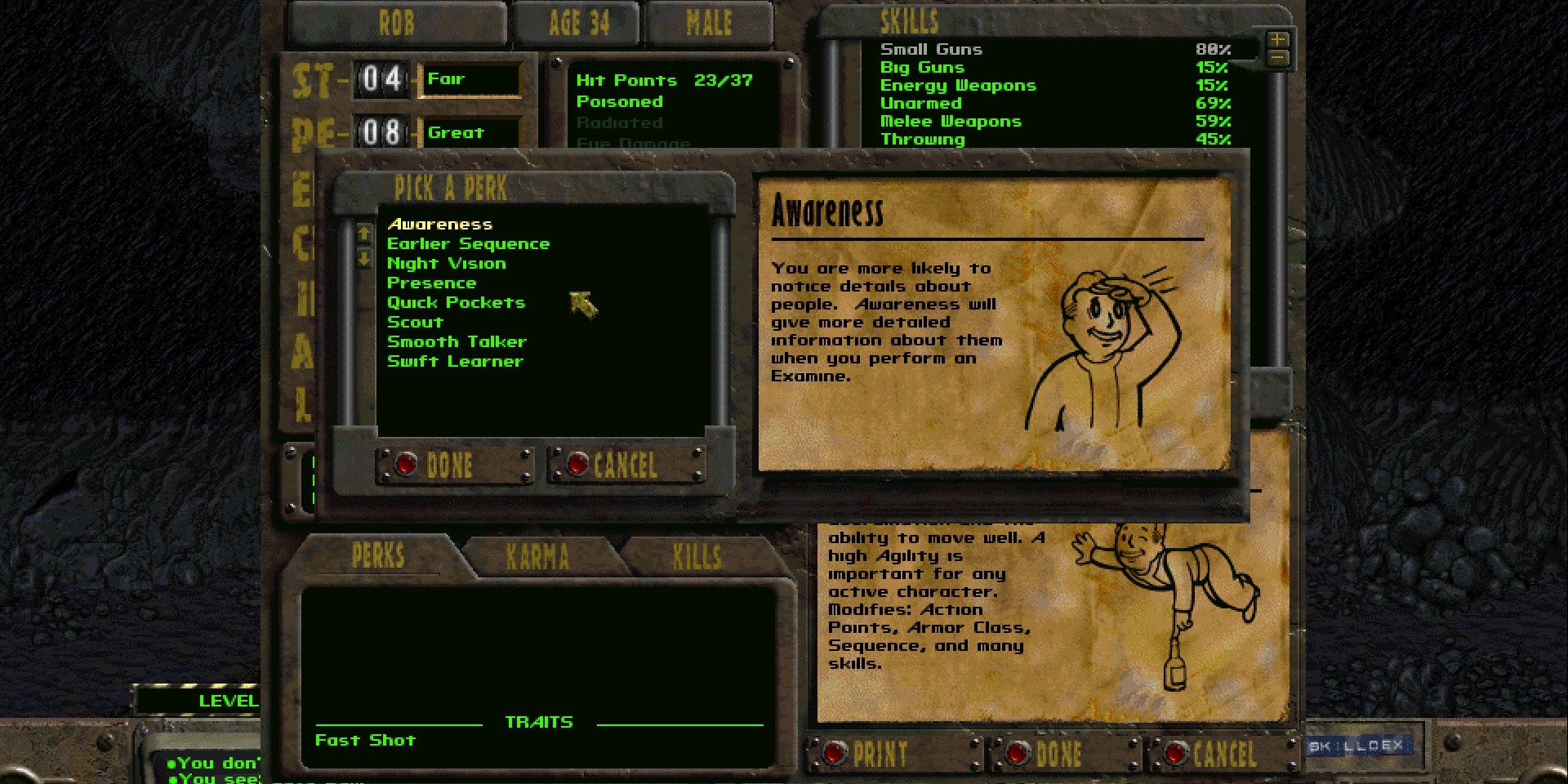

For a start, the Fallout team created a world with incredible freedom and reactivity to player actions, on the kind of level that even great RPGs like Skyrim and The Witcher 3 dared not strive for. Your choices could shape the future of a whole town; you could join a Raider gang by killing off their female slaves, or you could save the slaves and potentially gain yourself a companion; you could even - quite literally - talk the endboss of the game to death.

Modest as ever, Cain says that such system complexity wasn't all that hard to achieve. "In some ways it was easy," he begins. "It started from the idea of a locked door. I wanted there to be lots of ways to get through it other than picking the lock. I want you to steal the key from a guard or buy the key from a guard, bribe him, kill him and take the key, or use an explosive on the door and blow it open. What was cool was once you had it working on one door, it worked on all of them, and then we extended that to other things, like quests."

"Using the Wasteland IP sounded like a great idea, but it didn't direct our trajectory at all."

"It all came from the idea that you could talk, fight, or steal your way through the entire game," Boyarsky concludes.

Even as the project was continuing apace, with no notable roadblocks in development, the game's completion was far from assured. When Interplay acquired the coveted Dungeons & Dragons license in 1996, resources at the company were quickly funnelled towards D&D games. "Interplay were like 'we don't need Fallout any more, let's get your team reassigned to - I think at the time it was - Descent to Undermountain," Cain tells me.

The Fallout team was told that the marketing for the two games would cannibalise both, and Cain threw every justification he could at Brian Fargo to try and save the project. "I said 'the settings are wildly different, the mechanics are different, RPGs have long tails and people play them for years. We're cheap, and you can make double the money," Cain pauses. "I didn't know if I was right, I was literally begging."

Cain managed to persuade Fargo of Fallout's merits, and with so much of the company's attention being on their new D&D ventures, development on the relatively small-time project was allowed to continue unabated. In fact, Interplay was so preoccupied that only at the last moment did the Fallout team run into issues with getting the game released in Europe, when it was stipulated that they had to remove children - who were as killable as any other NPCs - from the European version of the game.

Given the moral panic around violence in games at the time, it's probably only by merit of Fallout's relative obscurity as a PC RPG that the game didn't get into trouble with more conservative elements of the media at the time, but of course this was never a focal point of the game. It wasn't so much that Black Isle made children killable, let alone encouraged the player to do so, more that children weren't explicitly protected by the game's systems, and were programmed in with the same parameters as NPC adults.

"There's nothing in the game that makes you be violent," says Cain. "in fact, you can play the game as a pacifist, so when people say 'Oh my God, the game lets you kill children, I'm like 'that's a nice way to reverse the fact that you killed a child." Luckily, none of the children in Fallout were quest-critical, so it was just a case of removing them from the European release.

In contrast to later games in the series, where your wasteland wanderings are often accompanied by crackly radios playing Jazz, Blues, Rock & Roll, and other old-timey tunes, the soundscape of the original game was far more ominous - sirens, static, what sounded like high desert winds interspersed with the distant wails of people (or ghouls). It really encapsulated the horror of stepping out from the safety of a vault into the great unknown of the wasteland for the first time.

Interestingly, this unique soundtrack stemmed from the fact that Tim Cain worked in a giant room affectionately known at Interplay as 'The Pit,' which he shared with 14 other people. "You cannot program in a room where people are constantly talking and a fax machine is going off, so I always had headphones on and played ambient music," Cain remembers. "I had so much of this music that I gave the list of my music to Mark Morgan and said I wanted the game to sound like this." Included in the list were Brian Eno's Discreet Music, Ambient Works 1 and 2 by Aphex Twin, and a CD called Ambient 4: Isolationism.

Each quest had myriad solutions, each NPC in the game could be killed, all the systems and mechanics were steered towards the kind of multiplicity that's still capable of surprising both players and its own creators "We put in mechanics and the QA people, and were so shocked at how they would use them," Cain tells me.

Even now, 25 years on, I manage to surprise Cain and Boyarsky when I recount my assassination of the High Priestess Jain by placing a timed bomb in the desk in her office then walking on out of there and letting it go off. "See, I love that you did that, and people say they like that, but over time games have become more ‘Hey, there's a symbol here that says this is a quest giver. You get given a quest, you're told exactly what to do,’" Cain tells me. "People say they liked what Fallout did, but when they actually go to play games, the ones they buy are the ones that the majority of people seem to be more attracted to - 'just tell me what to do and I'll do it.'"

"Interplay were like 'we don't need Fallout, let's get your team reassigned to Descent to Undermountain."

But RPGs today are a blockbuster genre, designed for the mass market and selling on the ideas of sprawling, detailed worlds, tons of sidequests, and often 100+ hours of content per run. Back in 1997, not only were Interplay's RPGs a niche, they were aimed at a relatively small subsection of a relatively small PC gaming market. You could even argue that Fallout (along with its sequel, and Interplay's slightly later Infinity Engine games) was a pivotal moment for RPGs, raising their profile to set them on the trajectory towards where they are today. The Fallout series itself, after all, has grown into a modern-day blockbuster, which inevitably means it exhibits those glitzy qualities at the expense of the subtle systemic charms of the earlier games.

"We didn't have to sell that many copies, and it's not like Interplay was spending a lot of money on it, even at the time," says Boyarsky. "Today, you couldn't start up again for the kind of money we had for the whole game. Companies are spending sixty, seventy, $100 million to make an RPG that's a AAA project and a flagship title. It's the biggest project a corporation is going to release that year, there's a lot more riding on that, so you need to have a wider appeal, you know?"

While Brian Fargo never got his wish of making Black Isle's project into a new Wasteland game, he did still end up having a vital input into the game's identity. For a good part of development, Fallout was going to be called 'Vault 13' but Fargo, planning ahead, questioned what would happen should there be sequels to the game - does it become Vault 14, Vault 13 2? In early 1997, not long before the game's release, Fargo suggested that they call the game Fallout. "At first, I thought 'well, there's no fallout left in this radiation, but then I thought about it for a while and I really liked it," admits Cain.

The rest was history. Fallout released on October 25, 1997 to critical acclaim. The game was released almost through the back door at Interplay, with Cain saying it had almost no marketing, no press interviews, and "I think just the one ad" before shipping. "What's hilarious to me is that people at Interplay would say 'oh no, we always loved the idea.' It's like 'no you didn't.'"

Like the Vault Dweller emerging into that New California wasteland for the first time, Fallout was a game that more or less had to fend for itself. And once it emerged, it changed the RPG paradigm forever.

.jpg)

.jpg)