It'll come as no surprise to many that Omori, the new indie RPG made by Omocat, is inspired by the Mother (Earthbound) series, among other RPG maker games such as Yume Nikki. But Omori goes beyond, transcending these classics, and leaving a mark on indie games in terms of injecting emotional expression into areas that AAA developers would never think of.

This article will include some spoilers.

You'll get the most from Omori if you tackle it blindly, and try to grasp the complete picture bit by bit, getting exposed to all the hints and surprises left everywhere by the developer, even on the start screen.

Omori is a retro-inspired RPG maker game about a group of childhood friends, or more particularly, a story about the friendship of children. The game starts from the perspective of the titular character, who is having fun with his group of friends: Kel, Hero, Aubrey, Basil, and Mari. Their way of having fun is arguably the most intriguing part of the story. We see all of them playing in a park filled with magical trees and otherworldly creatures. In addition, Mari is always sitting down and observing them, never moving an inch. The picnic basket Mari is holding beside her is the place where you can save your progress and heal your party from any damage. This will be very significant later on.

Shortly after leaving this dreamy world, you discover that all of this is happening inside your head as you sleep. Reality is very different from what the game has established in the beginning. Your friends are all grown up and more distant than ever. To top it all off, Mari is nowhere to be found. You learn that she passed away in mysterious circumstances, and that seems to have turned your world upside down.

Quickly you being to understand. You were dreaming of a time long gone. A time where you were all friends, and where Mari (who turns out to be your sister) was still alive. Moreover, everyone else seems to have chosen their own coping (or escaping) mechanism, which has influenced the way they talk and feel about things around them, and how they feel about you too. In order to resolve this complex web of mysteries, you have to travel between the real world and dream world in order to get the full picture, and then decide how you want your life to proceed, either by facing your past, or rejecting it.

Omori immerses you in the worldview of a child. It doesn't explain that you're taking on this perspective, but instead shows you that in every possible way, and relies on subtlety and ambiguity to convey the message. It's fascinating to be put into a viewpoint that you've long since forgotten about. Some things become so internalized within us that we're not aware when we're seeing the world around us from a new perspective. It's not easy to reclaim the emotions and peace of mind we had when we were younger, without all the external noise.

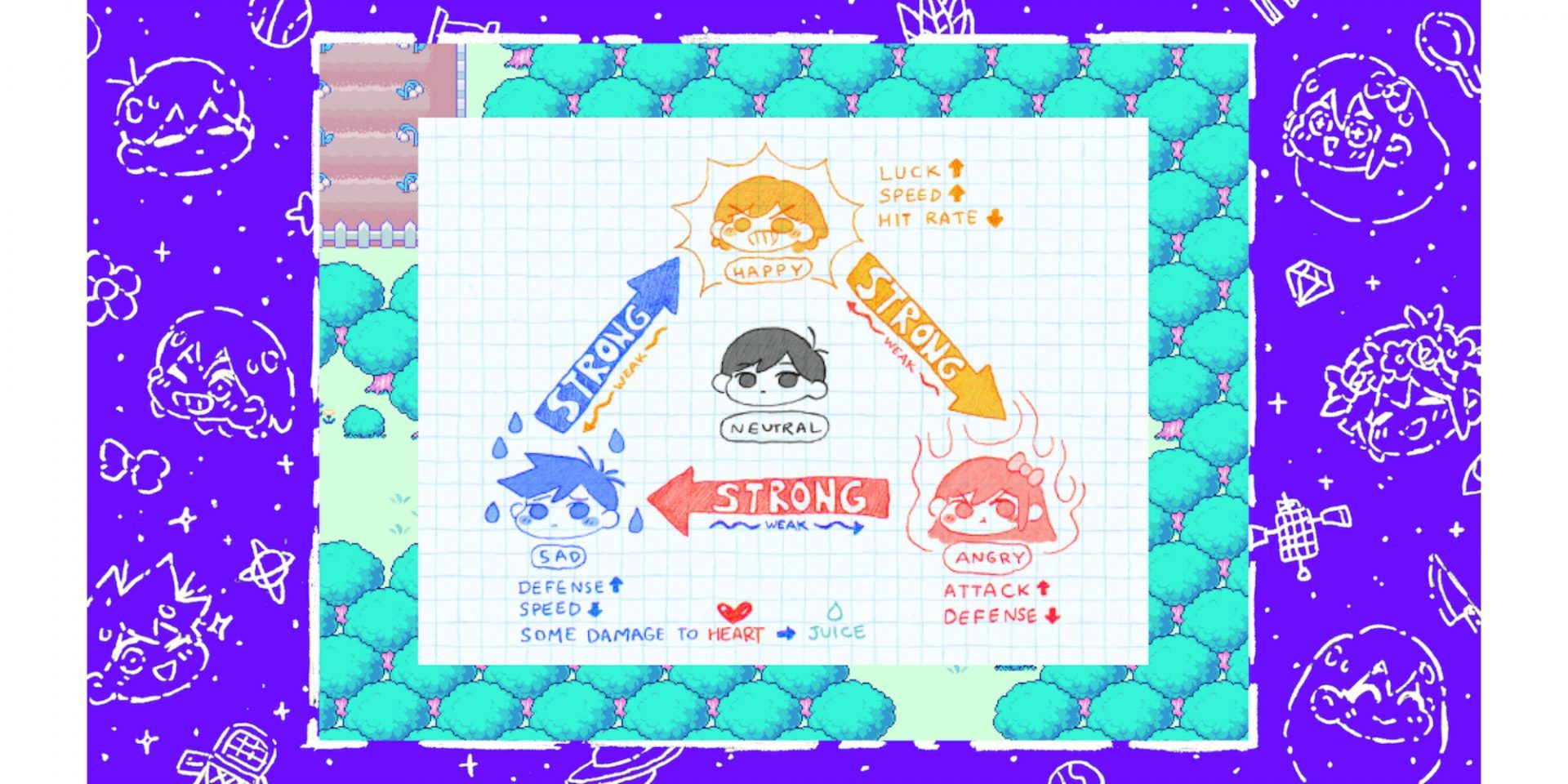

Nevertheless, Omori takes it to the next level. For example, tying the whole otherworld concept and its symbolism to the emotions of each individual member of your group. It's also clearly reflected in the Emotions chart what each of them primarily feels in their attempts to cope with Mari's death, and its repercussions. Converting their internal feelings, their strengths and weaknesses into mechanics is a refreshing departure from the traditional JRPG combat system in games like, say, Fire Emblem.

Where Fire Emblem defines your units mainly by their class, with their personality not having any meaningful influence in battle, in Omori you have to be aware of the moods and likes/dislikes of everyone in your team, and even the mood of your enemies. There are many special skills and battle scenarios based on that, and it is all portrayed depending on how the story and the narrative presents these characters, and how mentally well you are at any moment.

Earthbound was more about the external world than the internal one, looking at how the children get caught up in the negative aspects of adults as they grow up; their traumas, their powerlessness, and the society they grew up in.

Omori's world is much simpler, perhaps influenced by how Easterners view self-growth compared to the Western perspective that dominated Earthbound. Multiple research papers like this one actually tackle the dichotomy of how Eastern people view the self differently. It revolves mainly around accepting that the self has both positive and negative sides. This is clearly seen from the start in the availability of two possible routes: The Omori route and the Hikikomori route - on the first route you come to terms with yourself, on the second you surrender to your other self, made up of past traumas and coping mechanisms.

Defining each route through the mechanism of opening the door to your friend Kel, or keep it closed sent a very good starting message about what the game wants to convey. It's extremely clever how the different areas you are not allowed to access are blocked by your own negative traits and childish phobias, like spiders and drowning. The horror aspect of the game is subtle, its primary intention is not to scare the player himself, but instead to portray what your character is scared of, and help you understand him. This point is very important for characterization, and it flowed nicely with the mechanics and story.

Omori should be played by every parent who struggles to see things from their child's point of view. Even couples could use it to gain more insight into how each of them sees things. It does not rely greatly on satire with small hints of seriousness (like, say, Undertale does), but it has a very clear positive message.

Omori Is Always About You

The main final boss in Omori is not an external one - not an evil dragon or a wicked sorcerer plotting to destroy the world, as is the case in many other JRPGs. The final boss is none other than yourself, and the ending segment feels like a concerto to 'moving on' that deserves to be put into a museum. The game was always building to this climax from the first moment. It always feels like you have been living in the final battle, and gradually going through the required steps to defeat your sadness and worries once and for all.

Every step of the journey felt integral to your success. It was always about you and your team of friends, and their dynamics. They're not rigid nor robotic, and since the other world is also about them and your history together, you get to learn a lot of new subtle details about your friends everywhere you go, like Hero's nickname or the orange juice he dropped, which ties into a side quest about an Orange guy in the Otherworld. Even towards the end, you actually discover that you never really knew anything about Aubrey and her past, until you yourself decide to care and be proactive about it.

It's like the reverse of normal JRPGs when the character starts as a clean slate (usually suffering from amnesia) and each party member's story is actually confined in their own arc, never to be addressed again. Here everything is integrated very well and it makes each moment feel alive.

It was such a power move to fill Omori with this number of NPCs, each with their unique lines and jokes. Every party member, meanwhile, had a comment on every situation with all NPCs. Beyond the talking, the game is filled with many silent artistic scenes that leave you to interpret them, like your sister saving you from drowning, and other similarly powerful moments.

Farewell To The Old Me

Everything in this game will make you reflect on it, or think differently about it after witnessing it the first time. Boss characters appear again in different contexts, like they are living in the same world as you, and going through their own journeys. Puzzles are also mixed inside the dungeons and they are not just all a repetition of battle/story/battle. Many times you won't even need to lift a hand to resolve an encounter - some kind words will be enough.

It's a beautiful journey towards empathy and self-understanding. This theme is mind-blowing (and probably life-changing) once you notice the severe lack of boss fights in the Omori Route compared to the Hikikomori route. Because in the true (Omori) route, you understand that everyone comes with their own struggles and scars, so there is no need to fight them; in the route where you trap yourself in your own home (literally becoming a reclusive Hikikomori), you solve all your problems with force - another reason why the player can't let go of the Knife.

The Knife is the main battle weapon you find yourself holding all the time, and can't switch it out or let go of it unlike your friends, whom you can switch what they are holding on the go. The knife as we know is a sharp object that can hurt people, and using it, especially in your depressed mental state, can lead to severe consquences. At many instances you are shown to be using this knife to hurt others and even yourself, so in a way, the journey is not also about trying to move on from the past, but to be aware of how much you are hurting yourself and others by keeping attached to these tormenting memories.

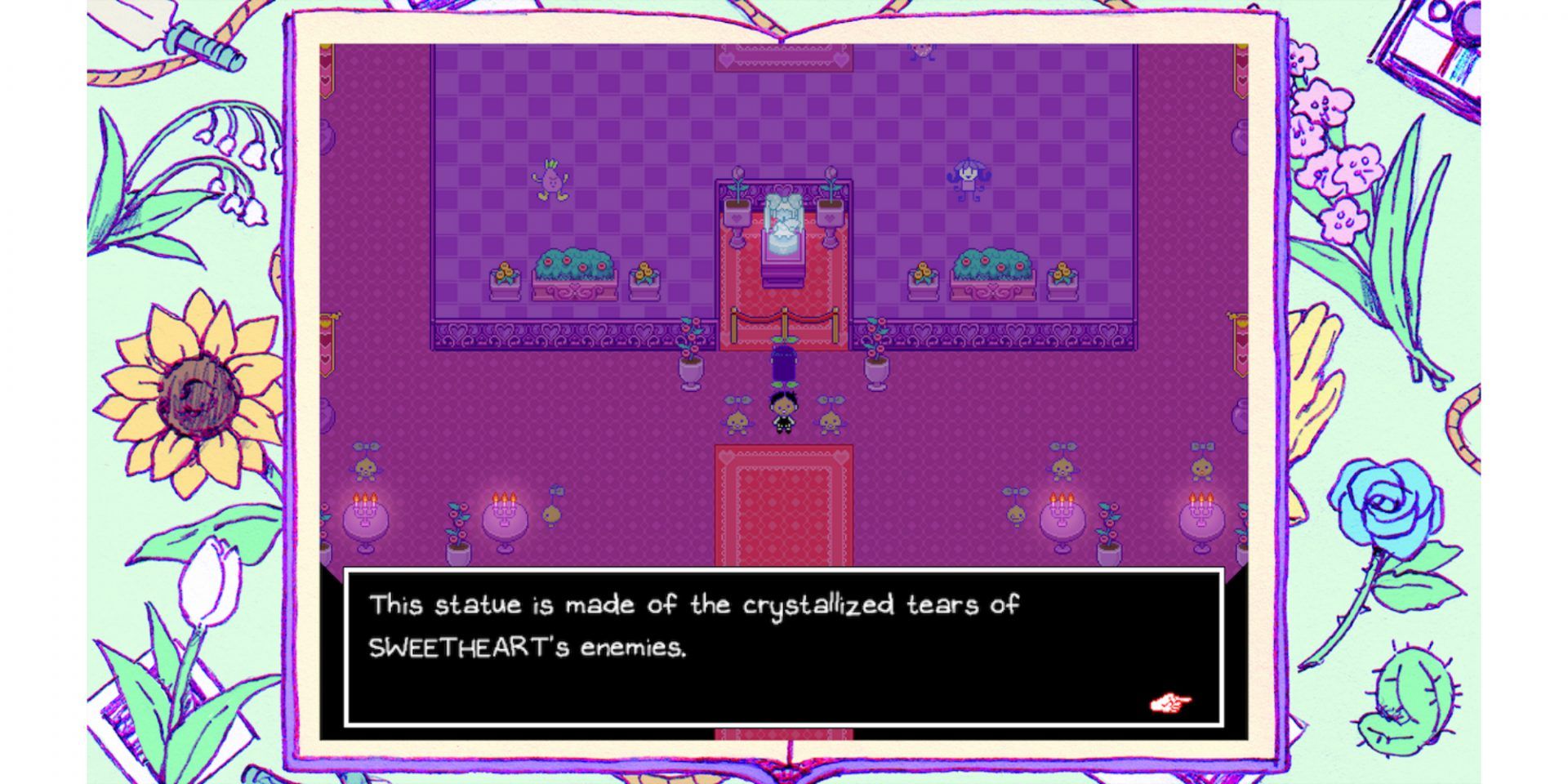

Omori's design also supports this symbolic message. The main difference in the route system reflects this, and how each dungeon has multiple layers of intertwining narratives, not all of which are centered around you. There is the Sweetheart plotline with the witches, your gang starting to lose their memories bit by bit, all the NPCs and their funny comments, and the player interpreting how these aspects reflect the real world. There is a lot to digest in just a single dungeon, and a lot of elements are left to your decision making.

It's also supported by the smart design that there is actually no clear distinction between areas populated by NPCs, and areas populated by enemies. Both are one and the same, which makes it always exciting to traverse new places. Even the optional content around the game follows the same premise of you learning to care and identify with others through overcoming yourself. How will you choose to deal with each single character or substory, and not only the major decisions, will determine major points in your character development.

The final detail that cemented Omori as a breakthrough in game design is none other than the save system. Another aspect that was carefully prepared with the picnics you get to do with Mari, and how she is always waiting for you after each hard trip. It isn't until you get to visit her grave and decide to have a picnic in front of it that it hits you how much you got used to her graceful presence throughout the game, and how far you have come. From blaming yourself for her departure, to vowing to keep her memory alive.

Everytime you finish a dungeon, you always find Mari waiting for you, showering you with words of love and kindness. Furthermore, if you actually choose to sit down with her and "have a picnic", characters will speak about their worries regarding the present narrative or location, and Mari will assure them like the big sister she is. This happens at all save points in the dream world without exception, but in the real world, Mari is not there, and no one really handled that truth to well. Instead they chose Anger, Isolation, Self-harm and many other things.

Visiting Mari's grave is also an optional choice left to the player, and might be the most important one in the whole game. Mari used to handle everyone's worries, point out their good traits, and reassure them when they are crying or afraid. In other words, everyone was completly dependant on her. Moving on from Mari's death means also growing up from the things that held you back. Otherwise, you can't stand in front of her, and tell her that everything is okay, and she does not need to worry anymore.

This final scene is a combination of everything you have been through. You have finally gathered your friends again, you overcame the things you were afraid of. You identified their core and the things they were missing and helped them heal and overcome them. In short, you did what would Mari have done if she were alive, and so, having a picnic right beside her grave, even if she is not there, feels like she is always there. Because you are living by the lessons she left, and upholding the wishes and ideals she wanted everyone to have.

This is just one example of the many optional side quests and activities that are also incorporated seamlessly into the never-ending stream of consciousness that is your soul. Omori is also one of the very few games you would actually feel the need to finish everything in it, explore all the other possibilities and endings, and finally fix what was broken.

Every chapter of the game felt like talking with a dear friend, and at no moment did the game get stale. Omori is now available on Nintendo Switch and Xbox Game Pass, and I strongly suggest you experience it (and perhaps glean your own meaning from its dreamy world of symbolism).