Editor’s Note: This feature will dive into spoilers for the story of Prey, so come back and read through after you’ve finished the game if you haven’t yet.

My first playthrough of Prey from developer Arkane Studios was in late 2017 as one of the first games that I rented via GameFly. I had just tried out the service as a way to spend less on video games, expensive as they can be, and wanted to try out Prey due to its mixed reception (though we liked it a lot at DualShockers). After completing my first playthrough, I was unimpressed. The combat was messy and only exacerbated by a late game introduction of hostile operators. The final twist is a narrative device I have less and less patience for, and the length was several hours longer than I felt appropriate.

And yet, this past month I found myself drawn to it again, buying a cheap copy from GameStop and rapidly playing through it again, ending with about 30 or so hours. While some of the problems from my first playthrough remained, knowledge of the way things work helped alleviate those issues and let me focus more on the thematic content of the game, which I found worthy of digging into.

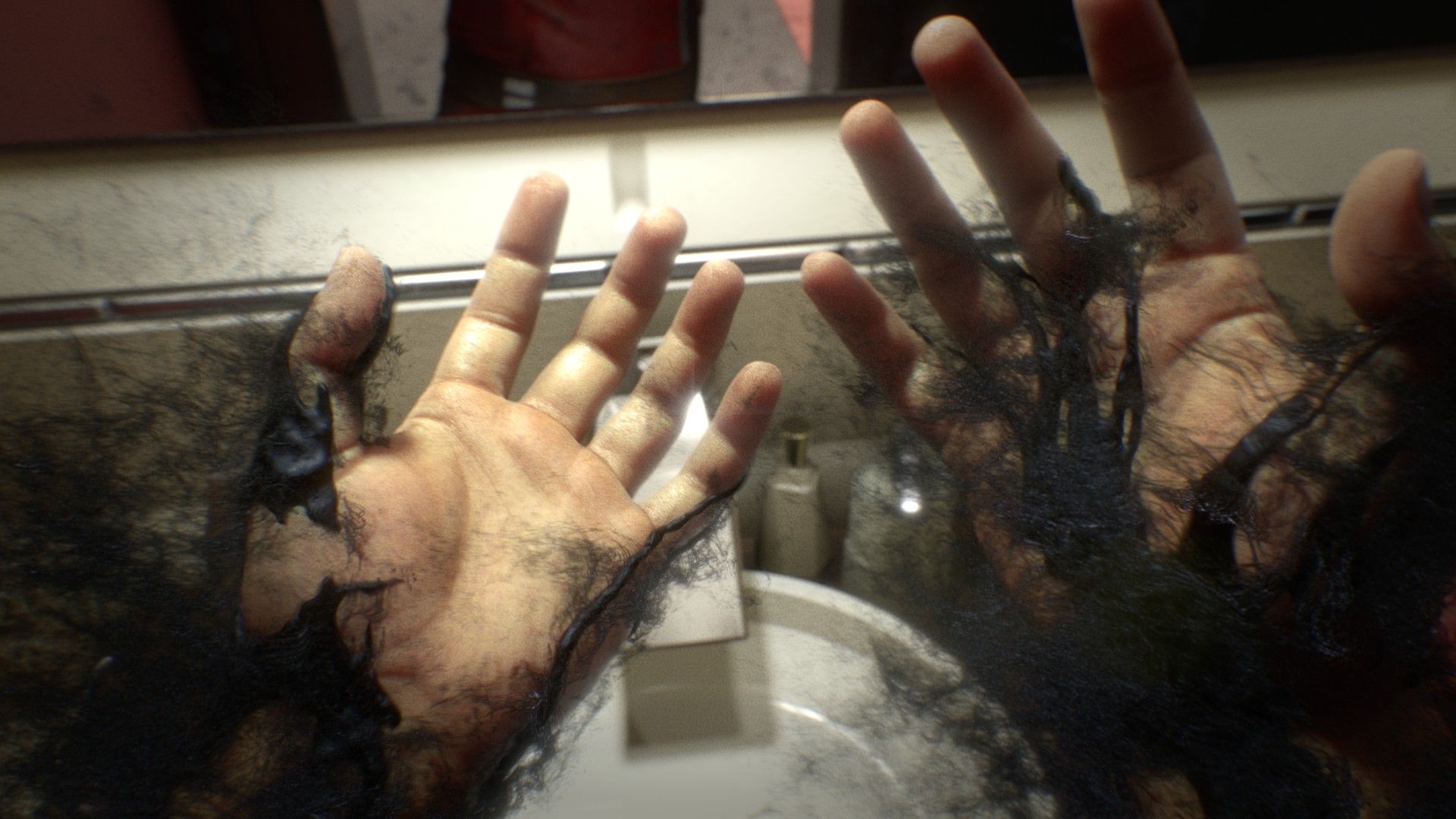

The first major twist in Prey is when you use the wrench to break through the glass window of your apartment to reveal you weren’t in an apartment on Earth, but instead inside a simulation within the space station Talos I. This deception early on reorients your perspective, and that same twist is utilized again, on a much larger scale, for the finale. Turns out, the entire adventure aboard the Talos I was nothing but a elaborate simulation itself, designed to test empathy within you, a Typhon presumably abducted by Alex Yu and tested with a Looking Glass simulation, based on Morgan Yu’s memories of the disaster. Key characters’ voices come out of various Operator frames, recounting your actions aboard the Talos I, and judging whether they have succeeded at teaching empathy to an unempathetic being. Early on during your journey, Alex tells you, “For all their wonderful abilities, there's one thing we can do that they can't - empathize with the suffering of another living creature.”

[pullquote]"This attempt at teaching empathy to the player makes Prey fall into the greater conversation of technology’s role in teaching empathy to those who lack it."[/pullquote]

This fear of encountering another sentient species incapable of empathy is also a real problem with the development of Artificial Intelligence. That fear is best embodied within the fictional Skynet, a sort of touchstone for everyone warning of the development of computers who lack empathy. It is something currently incapable of being taught to a machine, and in Prey, to the alien Typhon.

This frame within a frame can be extended further, with the game being a complex system of tests to determine whether the player herself has empathy. A final decision remains, whether to take Alex’s hand in cooperation or to kill him, completing the genocide of humanity by the Typhon. This attempt at teaching empathy to the player makes Prey fall into the greater conversation of technology’s role in teaching empathy to those who lack it. With the development of virtual reality headsets, people can be transported to anywhere in the world and “experience” the lives of others. Whether this is effective at instilling a sense of empathy in reality is undetermined, especially when applied to those beyond the developmental ages of schooling. Focusing only on Prey, does it succeed as a video game teaching and testing for empathy in the player?

[pullquote]"Works of fiction can even be overtly about provoking empathy but fail to force that connection between fiction and reality in their viewers."[/pullquote]

Those key figures who appear to pass or fail the player are in-game characters whose stories mostly center on tragedy as a way to teach empathy; Dr. Igwe is trapped in a storage container outside of the cargo bay, Danielle Sho lost her lover to a volunteer posing as the kitchen cook, Mikhaila is your ex-girlfriend and requires medication to live, Sarah Elazar requires help defending survivors, and Aaron Ingram is a convict you can unleash a mimic on. All of these are situations that ask the player to either make an effort beyond their needs to help another, or simply leave them to die.

As in most games, and reflective of reality, moral goodness requires more effort than its opposite. Each of these choices have payoffs, though, that incentivize good behavior: rewards in the form of neuromods, the currency of upgrades, other loot, or opening up opportunities for the different endings. This line of thinking is addressed by the finale, as one of the Operators will speculate as to whether your choices were selfish in origin or not, though another states it matters little given that it is impossible to determine. Though, is it important to determine whether or not decisions were truly altruistic? If games did not have a history of obsessively rewarding players for every good decision, a sort of Pavlovian reaction embedded within our collective game playing id, we would likely still choose to be good since it's all artificial and not real.

BioShock’s overly simple moral decision is one of immediate payout or larger investment. Harvesting Little Sisters results in immediate Adam, but saving them will reward you with more Adam later down the line. Even without that in-game reward, I doubt players would have chosen to Harvest over Rescue. Mass Effect’s player data showed that 64.5% of players chose Paragon over Renegade, a system that presented itself as less good and evil and more good cop, rough cop. InFamous had more players completing the game as a Hero than while Infamous. Prey itself has more players attaining the Do No Harm trophy over killing every human on or around Talos I. Given moral choices, players will more often than not choose the more upstanding one, though whether this is a reflection of their actions in reality is undeterminable.

[pullquote]"Given moral choices, players will more often than not choose the more upstanding one, though whether this is a reflection of their actions in reality is undeterminable."[/pullquote]

Teaching empathy is generally regarded as something done during the early stages of development in children, and generally not through the subtext of works of fiction. Much like the “Wow cool robot!” meme, many pieces of media I have watched or played as a child through to high school had subtext I was incapable of picking up on until I was much older. The eco-terrorism of Final Fantasy VII is much more prescient now as climate change lingers over our immediate and distant futures. Other examples of subtext going over my head are the grey morality of needless wars in Ace Combat 4: Shattered Skies and the libertarian failure of Rapture in BioShock. I don’t think as a 10-year-old I would have understood that Prey’s side missions were testing for empathy for these digital creations, much like I didn’t on my first playthrough in 2017.

And even then, works of fiction can even be overtly about provoking empathy but fail to force that connection between fiction and reality in their viewers. Much like my parents can empathize with Michael Clarke Duncan’s character John Coffey in The Green Mile but fail to approve of Black Lives Matter and the challenges facing people of color today, many people can easily watch and be affected by movies portraying actual events but fail to carry that into reality. Showing an adult a VR recreation of the Syrian Civil War from a refugee’s perspective will be unlikely to cause them to change their minds over asylum seekers and other “illegal immigrants.”

Even within myself, I questioned the validity of the choice of Talos I’s fate. If it was simply a simulation, why should I care if I chose to destroy it or save it? The moral choice presented here is: one, to blow up the station and erase the information about the Typhon within, tainted by the blood of countless “volunteers” (in actuality, convicts from a brutal Russian justice system) and hidden corporate agendas from Alex Yu, the cyberpunk-ian Board of Directors, and your past self. Or two, salvage Talos I, keeping the research intact and hoping it will lead to a better future instead of abuse and exploitation at the hands of your own company.

[pullquote]"Prey might be a fictional game, but making the campaign itself a work of fiction within itself renders its teachings mute."[/pullquote]

A book expounds on the existence of space elevators, with land of potential future sites being bought and squatted on for profit. This might be a future of great progress thanks to JFK’s averted assassination and cooperation with the USSR, but capitalism still reigns. All of these factors took on less weight when I realized they didn’t matter, as the end remains the same: Earth is overrun by Typhon coral, and Alex is the only one alive despite his bloodied hands. This is partly why my initial decision was to kill him: his well-meaning deception didn’t clear him of his crimes, and it’s just a game anyway, right? This ending decision can even be interpreted as Arkane acknowledging that even if you were the most empathetic within the game world, the option and execution of violence is still available and can still occur outside of it.

Despite just being a game, there are plenty of other games that have evoked emotional investment from me, from the aforementioned Final Fantasy VII to The Witcher 3: Wild Hunt. I cared about the digital avatars in those worlds despite knowing fully well they were works of fiction. I also cared for Danielle’s pain over the loss of her love Abby, but her ultimate fate tied to the space station is disregarded when it is rendered as a deception in the final twist.

Prey might be a fictional game, but making the campaign itself a work of fiction within itself renders its teachings mute. The disconnect between the digital avatars is similar to the disconnect to digital text and usernames online being connected to real human beings, something that has led to a lot of documented pain, studies, and questioning over the net effects of the internet at large. Empathy can be hard to test for in terms of increase or decrease within the general population, even with the current political and social climate often testing those limits. I don’t think Prey, phone apps, VR simulations, or any amount of moving films about underprivileged populations is going to change that.