Kratos, Nathan Drake, Master Chief, Solid Snake, Cloud Strife, Ryu Hayabusa, Gordon Freeman, Samus Aran, Lara Croft, Marcus Fenix, Link and even Mario - all of these iconic video game characters have something in common. Besides the obvious fact I just mentioned (that they’re all video game characters), they all share a common trait: they use violence to achieve their ends.

Is the fundamental reason for this violent behavior merely a response to being victims of extreme circumstance? Or are our beloved heroes merely selfish thugs, lacking compassion and remorse of any kind? Kratos is a tormented soul, haunted by the deaths of his wife and child, who seeks vengeance via the destruction of those he deems responsible. Nathan Drake is a life-long adventurer, willing to lose everything and kill anyone who stands in his way, in the hope of discovering the most sought after treasures of the past. Mario repeatedly takes it upon himself to rescue the abducted Princess Peach, defeating everything Bowser can throw at him in order to reach her.

Games that explore unique worlds and tell compelling stories, like any other storytelling medium, have proven to be extremely popular. They place us in the shoes of characters and worlds that we could only dream of, and others that we hope never to see. A beautiful looking game world can quickly captivate a player, but in order to maintain their intrigue, the characters that inhabit that world must react in ways that are conducive to that world. When Kratos decapitates a Minotaur, we expect a different emotional reaction from him, compared to Nathan Drake shooting a fellow human, or Mario, jumping on top of an unsuspecting Goomba.

Mario games are always rated as suitable for a large age bracket, unlike games such as Uncharted and Gears of War, which are limited to a more mature audience. There is obviously a distinction between the content in these games. The reason for Mario’s broad acceptance being that the world, the environments and characters are so far removed from reality that most people aren’t so quick to equate them to things that exist in our world. On the other hand, when Marcus Fenix stomps through the skull of a Locust, resulting in an eruption of bodily fluids, the connection to our world is considerably more palpable.

A problem that arises in games that feature violent protagonists who are designed to represent real-life human beings (Solid Snake, Lara Croft), is that when a sane, emotionally stable person kills someone, it’s something they must live with for the rest of their life. It’s not something you can easily forget, especially if it’s outright murder, rather than in self-defense. Of course, I can’t speak from personal experience, but war is hell. I, nor most people, could ever come to understand the true horror of war, and we should think ourselves lucky for that. For those that do, though, it can have a devastating effect on the mind. You only have to look at the current suicide rates of U.S. veterans to understand this.

For violent protagonists in games to maintain a semblance of humanity that players can identify with, they must convey realistic emotional reactions. Many of the characters mentioned at the beginning of this essay kill hundreds - maybe even thousands - of human beings during their games, but how do they deal with their blood-stained histories? Nathan Drake shows very little, if any, remorse for the countless men he kills during his adventures. However, that fact alone isn’t the major issue. The problem arises when Naughty Dog and other developers try to convey a sense of humanity and emotional vulnerability in their characters, despite the fact that they’ve just left a graveyard of bodies behind them.

If a developer wants to create a psychotic, murderous protagonist with no remorse, they’re free to do so. But don’t expect me to feel sympathetic when things don’t go their way. With characters like Nathan Drake, there are conflicting signals given to the player, which stem from a paradox of emotion. On the one hand, he is a caring friend, who would gladly take a bullet for his life-long partner, Sulley. On the other hand, Drake repeatedly chooses to place himself and often his friends in life or death situations, where they will have to kill countless strangers, for the sake of treasure seeking; empathy and rational consequence clearly fly out of the window. It’s as if Naughty Dog (and many other developers) are asking the player to empathize with a protagonist when they are in a tough situation, such as when one of their friends is hurt; showing them a cut-scene featuring convincing emotional responses via their expensive motion capture animation. Then, only to say, “Right, we need you to go here, so to make it interesting we’re going to put a hundred strangers in your way. Kill all of them and you can progress.”

This dichotomy between cut-scenes and gameplay sends conflicting signals to the player about the motives and values of the character they’re controlling. The character players watch during cut-scenes and the one they control during the gameplay segments appear to be two separate people. It’s a designer double-think that limits the power of a narrative and the characters that drive it.

It is clear that the Uncharted franchise was inspired by famous Hollywood action movies such as Indiana Jones, which is fondly remembered as an over-the-top thrill ride, teetering on the edge of plausibility. Viewers don’t tend to expect fully realistic, three dimensional characters in this type of entertainment. Is it the case then, that the actions of violent protagonists in games can’t be congruent with what we in the real world would deem to be realistic emotional responses? Will the need to have the protagonist kill throughout a game always exist in order to make it ‘fun’, or is it possible to create an action-oriented game that truly reflects the emotional turmoil that results from acts of murder? What about a game that only gives the player an opportunity to act violently on very rare occasions, if at all? Could a game still be compelling if only one person died in the entire game? Surely the death of that person would be hugely significant to the game’s narrative.

The fundamental question of this essay, and thus the one I deem more important, is why the act of violence is such a popular solution to our fictional characters’ problems? Is it purely the most decidedly entertaining type of gameplay for a player to engage in? Do gamers just want to feel empowered, for lack of control in their own lives? Or are violent video games merely a reflection of the West’s addiction to war and conflict? Obviously the triple-A, big-budget titles that inhabit the current market serve a demand made by a large proportion of gamers and thus there are plenty of players supporting the production of violent games. But consumers rarely know what they want.

A great entrepreneur or business is one that proves this, by creating something beyond the markets' imagination. Once people see a great new idea, they want it, but their desire is created by the entrepreneur or business. So is it the game companies that have identified and established video games as a primarily violent medium? Clearly they are giving a lot of gamers what they want, or what they think they want.

Arguably gaming has the highest concentration of violent content of any medium, even more so than the Hollywood film industry. Game creation is still a relatively infantile discipline though, so perhaps the industry will move beyond its addiction to killing in games.

Western culture often defines a hero via his/her physical might - how hard they can punch, how well they can shoot, how much punishment they can take. This archaic gladiatorial archetype is continually manufactured by both the games industry and Hollywood. Again, film-goers and gamers seem to want to see protagonists prove their physical superiority more than anything else. Heroism in the real world, however, is often the polar opposite to this paradigm. Those that have looked beyond violent methods to achieve change, opting to use reason and peaceful negotiation to communicate ideas, are some of humanity's most treasured icons.

We don’t necessarily need to look to national icons, though, to understand heroism. Heroic acts can be found in every day life. A man/woman notices an oblivious teenager about to cross the street without looking and drags them back onto the pavement, a person in a supermarket notices a child being mistreated by an adult and speaks out against the abuser, a driver notices a broken down car in the middle of nowhere and stops to see if they can help the car owner; these are all acts of heroism in the real world and should be treated as such.

Now you may be thinking, “How on Earth can the act of helping someone fix their broken down car compete with an epic fist fight with your psychotic twin brother, on top of a giant robot you just destroyed?” The purpose of this discussion is not to say that violent, action-oriented gameplay has no place in the medium of games. However, game designers are selling themselves short. Gameplay centred around violence is only one out of an endless number of possible scenarios.

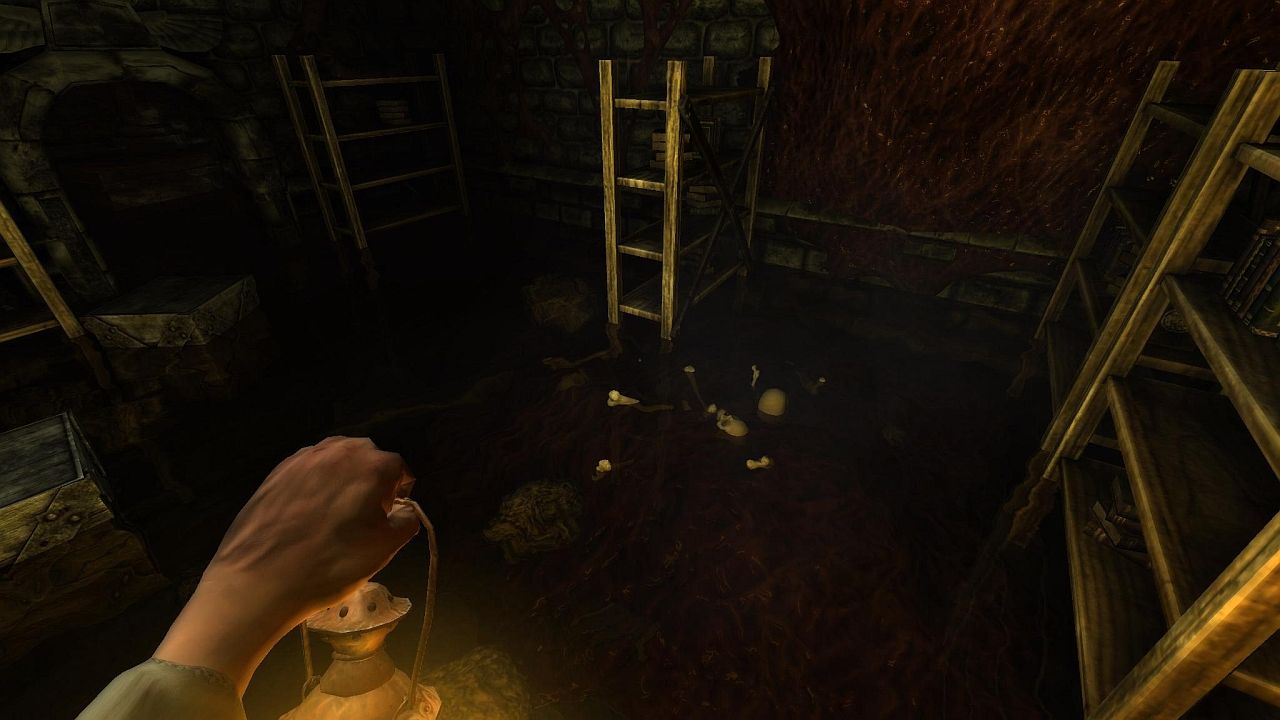

Rarely in games are players rewarded for avoiding violent situations. Amnesia: The Dark Descent was a cult hit that breathed new life into the survival horror genre. It put players in the shoes of a defenseless and shaken man who must navigate a tortuous environment, whilst trying to maintain a semblance of sanity. If players only enjoyed being empowered and feeling like a superior being, surely Amnesia should have failed.

The feeling of vulnerability in games is one that is often overlooked. Less is often more, regardless of the medium. The predictable progression ark whereby players become increasingly more powerful as they move closer to their overall goal has become stale and is largely a trick or illusion created by game designers. It is often the case that instead of gaining any noticeable improvement in skill, designers will merely tip the scales, or tweak the numbers. You are given a superior weapon, you can jump higher or take more damage. These are illusions of improvement that convince players that they’re making progress when really the gameplay is largely unchanged, requiring players to repeat the same actions, with only superficial differences.

The games industry has long enjoyed creating titles that put the fate of the world on the player’s shoulders. When a game asks a player to save the world, the solution is almost always war. A conflict that boils down to ‘us versus them’; “they’re coming to kill us and we need to fight back”. Compared to other storytelling mediums such as film and literature, the gaming industry seems to have pigeonholed itself. The opportunities to experiment with gameplay mechanics that don’t involve killing things in order to progress are being squandered. Rarely, if ever, do we see games discussing themes such as rape, child abuse, adultery, or abortion, which appear routinely in the aforementioned art-forms.

I accept that not all game designers are interested in ‘saying something’ in their games, or conveying a meaningful message or idea. Some designers just want to create crazy, exciting or purely epic situations for a player to enjoy. That’s fine. For those that do, I encourage an exploration of storytelling in games that doesn’t ask the player to empathize with a character, whilst simultaneously requiring them to massacre droves of NPCs, for fear of not being ‘entertaining’.